Session Zero: Why Children’s Literature?

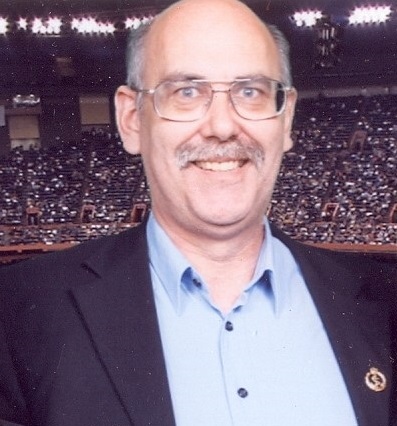

David Flin

It gives me great pleasure to (finally) continue the tradition of publishing guest articles here on The Scifi and Fantasy Reviewer. It’s my hope to foster a habit of publishing on this blog thought-provoking articles focusing on different aspects of writing, editing, publishing and even reviewing the written word. To continue the series after a rather long hiatus, returning guest author – and editor of the fantastic Sergeant Frosty Publications – David Flin has provided an article on the challenges found in writing literature for children, and the many complex, intermeshing elements of children’ lierature that reveal the myth of children’s literature being “easy to write”.

There’s sometimes a lot of opprobrium attached to writing for children and young adults. It’s often considered easy to write for children, and that it’s “unimportant”.

Children’s fiction has long been dismissed and patronised by people who really should know better. The late and unlamented Martin Amis once said: “People ask me if I ever thought of writing a children’s book. I say, ‘If I had a serious brain injury I might well write a children’s book’.”

When I tell people that I write books for children and young adults, I often get that look. It’s the same look I would get if I told them that I make bathroom furniture out of matchboxes for the fairies that live at the bottom of my garden.

The Guardian, that bastion of pretentious patronising sneering, wrote of the author Alan Garner: “He has never been just a children’s author: he’s far richer and deeper and intelligent than that.”

That’s putting children’s authors in their place. According to The Guardian, children’s literature isn’t rich or deep or intelligent. But then, when has The Guardian ever been right?

It’s nonsense, of course. In fact, I contend that it’s far harder to write for children and young adults than it is to write for adults. I’ve done both, and I certainly find it a lot easier to write for adults. Children’s fiction needs very tight pacing and internal consistency; it needs to generate a sense of wonder and autonomy for the children.

Martin Amis, expanding on his brain injury comment, said: “I would never write about someone that forced me to write at a lower register than what I can write.”

That whooshing sound you heard was that made by the point going over his head.

If you write down for children, “at a lower register”, it won’t work. I work at a Junior School (ages 7-11), and the children have very finely tuned patronisation senses. If they feel you are talking down to them, or if the story they are reading does so, they lose interest.

And God knows, having read academic works and Finnegan’s Wake, there are authors out there who demonstrably can’t write a clear, comprehensible sentence.

A plot has to be coherent and easily understood. It can be complex, but if there are plot holes, they will be spotted and the author can’t hide them beneath a sea of complex verbiage passing for depth. The author can’t just throw in an action sequence or a romantic encounter or a digression with a political diatribe to distract the reader, because the moment you do that with a young reader, their attention wanders and you’ve lost their immersion in the tale.

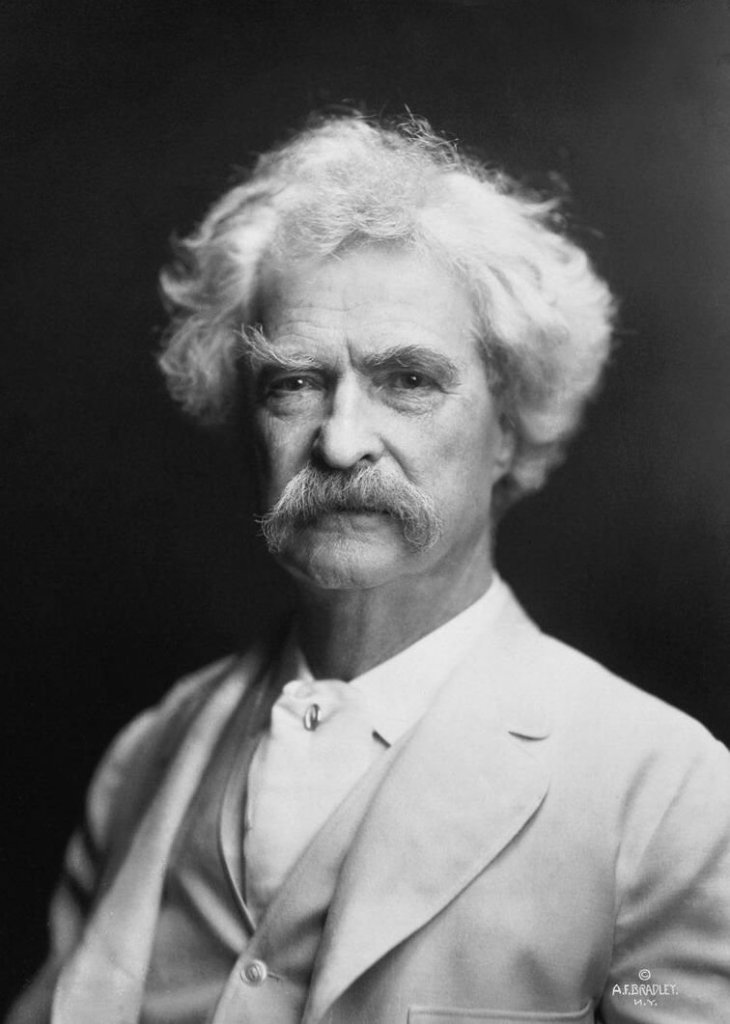

A book for children and young adults is an exercise in brevity. That can be a challenge, to pare a story down to its essential elements, to excise unnecessary verbiage, that’s not easy. Mark Twain once said: “If you want me to give you a two-hour presentation, I am ready today. If you want only a five-minute speech, it will take me two weeks to prepare.”

Mark Twain knew a bit about how to write for children.

The other feature about writing for children is that the reader is very well aware of what it is like to have neither autonomy nor power. They can’t drive a car or take part in adult sports (notable exceptions for people like Sky Brown, who won an Olympic medal in Tokyo in 2021 aged 13. I would have loved to have been her teacher when she got back and the class had to write the traditional: “What I did on my Summer Holidays” essay).

This means that the author has to devise a plot that takes these factors into account. You simply can’t have your ordinary child protagonist overpowering an adult antagonist without some major levelling of the playing field. Mark Twain demonstrated this with his books Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn.

Yet the author still has to create tension. That means they have to find plausible ways for young protagonists to deal with the obstacles they face. Good examples can be found throughout the Just William books by Richmal Crompton.

And, of course, there’s a strong correlation with good science fiction and fantasy and with good children’s literature. Both should engender a strong sense of wonder, both often involve fantastical elements which still have to follow their own internal logic.

Which is a rather long-winded way of saying that literature for children and young adults has value. Good books are good books, regardless of their target audience. The classics – Winnie the Pooh, Huckleberry Finn, The Jungle Book, Swallows and Amazons, The Railway Children, Kim, and many others – all completely immerse the reader. I’ve no idea how many meals have been missed by a reader being lost in the plot and oblivious to the outside world.

This rant has all been building up to say that I’ll be reviewing a variety of books written for children and young adults.

There are certain factors common to a lot of children’s fiction. Anyone who has had dealings with children, be it as parents, teachers, or whatever, know that there are three critical words that express severe displeasure by the child/children. “It’s not fair.” Literature for children is often shot through with a thirst for “justice”; the wicked stepmother is beheaded or burned in an oven, the villainous spy gets chopped apart by the propeller of his getaway boat, the witch is turned to stone.

Alongside this thirst for justice, there’s a sense of cooperative effort. The Loner who walks their own path and who lives by their own rules and who would be, if one is honest, an unpleasant person whose only redeeming feature is that the author has labelled them a hero – this is very much an adult invention.

By contrast, children’s literature is largely centred around friends cooperating. The Famous Five; the Swallows and Amazons; the Micronauts; Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy; Pop-Up, No-Legs, and Bandit; the Seven Dwarfs; Winnie the Pooh and all his friends; Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy; the list is endless. There might be a leading figure in the group (Harry Potter, for example) with a bunch of friends helping them, or they might be equivalent in standing with different skills (Daisy, Blane, and Rose from MI High), or they might be equivalent in standing with similar skills (Max, Cat, Ant, and Tiger from Project X). Whichever it is, there’s often multiple protagonists working together.

There’s often a surprisingly strong political element to children’s literature. These books are written for those without economic or political power. Children have no vote, no money, no control over capital or labour or institutions of the state. They live fully aware of their lack of power.

And, parallel to this, children also have no responsibilities. They don’t have a mortgage or dependents or need to earn a living.

This can result in a lot of children’s literature being subversive. William is forever pitting his wits against the Way Things Are; the same is true of Jennings, and Paddington, and Tom Sawyer, and Kim, and Mowgli, and countless others. It may be a very urbane rebellion, but it is a rebellion nonetheless.

Sometimes a rebellion supporting the status quo, and sometimes supporting chaos.

If you want to look at ways literature can both define and change the world, don’t go looking for the great polemics of literature. Look to the sword wrapped inside an umbrella, those books that have a strong core of showing what bravery is like, of hope and justice and fairness and cleverness and awe and wonder and friendships. That’s what you can get from these books. The books of our youth often shape the way we think. They are, if you like, our first impressions of the world.

In my first review, I’ll be looking at a classic, voted as the best ever children’s book in a survey conducted by Penguin books. It’s about a bear and his friends, and about a boy. The first book I ever owned, and – over six decades later – I still have those copies of the four books. It is, of course, Winnie the Pooh by AA Milne.

This is not to be confused with the animations that bear the same name and sometimes reference the same plots as the books, but which in no way connect with the books.

The Snow Marine Speaks – David Flin

I’m David Flin, and I have been for most of my life. I’ve read that with great age comes great wisdom. Well, I’ve achieved the great age (71, and I’ve sidestepped three certain death situations). Wisdom, not so much.

I’ve been a writer for nigh on thirty years now, and in 2020, I concentrated on writing for children and young adults. I also started Sergeant Frosty Publications which publishes books for children and young adults.