Today on The Scifi and Fantasy Reviewer I’m once again proud to publish the third in a series of guest articles written by David Flin, who is both author and editor at the superb new publishing house Sergeant Frosty Publications. Today, David takes a look at the world of Harry Potter, and specifically the first book in the series – Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. How does it work as a stand-alone story outside of the mega-bestselling series it kicked off, and how doers it so effectively write to its target audience?

Wizard Pranks In Wizard School

Magnus Reviewus by Sergeant Frosty, being a review of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, by JK Rowling.

Let’s get the awkward bit out of the way at the start. In reviewing the book, I am not making any statement about Rowling’s expressed views on subjects that have nothing to do with the book. Since writing the book, Rowling has gone on to fame and infamy, expressing views with the confidence of an expert on subjects she self-evidently is completely ignorant about.

It’s something that seems often to happen to people who become rich and famous for one thing, and who then start to think this makes them an expert in other fields. Richard Dawkins made his name as an evolutionary biologist, brilliantly explaining complex issues in that field for the popular market. Then he moved into less-informed dogmatic statements about theological matters.

Russell Brand is another who has been on a journey; from rock-star-type comedian to political activist to believer in global conspiracies to political activist for a completely different political stance, and currently on Christian Evangelism.

And, likewise, JK Rowling has gone from author of a book for children to responsible for a sprawling franchise, and now a vocal opponent of Trans-Rights, and a growing list of problematic views.

It’s one of the dangers of being successful and famous for work in one field. People start to treat your opinions with respect, and this encourages the person to think that because their views on their expert subject are of value, that all their views carry similar weight, regardless of how little they might know on a given subject.

However, I’m reviewing Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, not JK Rowling. This will be a feature of these reviews. I may well include books by authors who have problematic views on other topics (Rudyard Kipling, George MacDonald Fraser, Marion Zimmer Bradley). I’m reviewing the books, not the authors.

Onto the subject of this review. I’m looking at just the first book in the series, which was written as a standalone tale.

There is a very long tradition in British children’s literature of using boarding schools as a setting. The Jennings’ stories, St Trinian’s, Molesworth, Billie Bunter, Malory Towers – the list goes on. Goodreads lists 91 such book series. Some were purely humorous, others had stories and plots and characters.

It’s hard to explain why there have been so many books in this genre, given that boarding school is something only a small number of children experience, and those that do tend to be from a very narrow and privileged section of society. It’s all terribly upper middle-class and above, and something of an opaque setting to the vast bulk of potential readers.

All the children I’ve had dealings with (either as a Youth Club leader or as a Teaching Assistant) have great difficulties grasping the concept of saying goodbye to parents at the start of term and not seeing them again until the end of term. It’s easier for children to accept that there could be a portal to another world in their wardrobe, or that British Intelligence trains spies at a standard secondary school, or that a time-travelling journalist combats alien threats with the help of children she’s befriended from her neighbours.

And yet the boarding school setting is a popular one. I suspect that’s because it allows the author to draw the protagonist into a setting where they were removed from the support structure of their parents, and able to continue school adventures without the breaks for going home after the school day.

Starting at a strange school always strikes a chord with the child reader. It’s a scary time for any child; there are new routines to get used to, new friends to make, new lessons to master, new teachers. Everything feels much bigger than they’re used to; all the children except the new ones are bigger than they are.

The reader, therefore, is primed for the essential premise of the story. I have to say that this first book is an excellent standalone story. In many ways, it has parallels with the Star Wars franchise. The first tale is self-contained and stands alone, and draws upon stereotypes as a short-route to development. Subsequent tales grow increasingly tortuous, and start to fall apart under the weight of their own internal contradictions. The worldbuilding becomes increasingly erratic and the characterisation loses focus, to the point where by the end, I’m either cheering for the Bad Guys or shrugging “A Plague on Both Your Houses”, according to my mood at the time. And that’s not getting into the essential premise: A young naïve lad lives with his uncle and aunt, not liking the situation he is in. Along into the story comes an elderly practitioner of a secret magic, leading the protagonist into studying the secret magic while telling half-truths and showing disdain for the normal world. The protagonist later turns out to have a close connection with the main mystical villain (Darth Voldemort?) …

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone starts with a phase of the book that is essentially lifted straight from Cinderella. The protagonist is held in drudgery, treated badly by uncaring, obnoxious near-family who despise them, and whom we are meant to abhor in turn. Potter’s family go to considerable lengths to try and prevent his going to Hogwarts, apparently out of spite, because they don’t appear to want him around.

(Why not just let him go without a fuss? Then he’ll be out of the way for some two-thirds of the year). When you analyse the worldbuilding in the Harry Potter series, it steadily falls apart. However, for this first book, it doesn’t matter. We have a picture painted for in in bright primary colours of the classic Cinderella opening. There’s precious little subtlety in the depiction, little nuance, but this isn’t a tale involving shades of grey. This is a children’s tale intended to cause wonder, and it does so in a slender 223 pages.

The ”Cinderella” portion takes a quarter of that, 48 pages. It doesn’t need any more than that. Indeed, spinning this portion out would run the risk of committing the ultimate sin for a children’s book – boring the intended reader.

In broad strokes, we learn that Dudley Dursley is a spoilt bully, that Mrs Dursley is a snob of the first order, and Mr Dursley is an unpleasant tyrant towards Harry. What more do we need to know? It’s time to move into the next portion of the story, where we are introduced to the Wizarding World.

Straight away, we come across the concept that there is a wizarding world invisible to the non-magical (muggles), with an entire Ministry (the Ministry of Magic) devoted to ensuring that muggles don’t realise magic is real. Apparently this is because if muggles knew that magic was real, they would use it to solve all their problems.

This is one of those phrases that one can get away with in a standalone book of which this is a peripheral point, but which falls apart as soon as it comes under any kind of scrutiny.

We spend around 40 pages equipping Harry (it’s almost like equipping a starting character in a Tabletop Role-Playing Game) and getting a train to the school.

Then we have 60 pages introducing us to the actual school and the weirdness associated with it. Harry and Ron become good friends, later joined by Hermione. This is a crucial element of the book, as many children find it difficult to make good friends at a new school. Friendships and bullying are two subjects that greatly impact children at school, and those two features are front and centre of this phase of the book. The intended readership can relate to this phase of the book. Never mind magic and fantastical creatures and invisible platforms at railway stations; they can understand feeling lost and confused at school, not quite understanding the lessons, liking some teachers and not liking others.

It’s a great example of that old piece of writing advice: write for your target audience. The story aims quite neatly at both children just starting secondary school, and at those who remember the classic boarding school books of their youth.

The first indication that there might be a mystery involved comes on page 120 (over half way through the book), and the mystery starts properly on page 142.

Because that is what the book is. It’s a rather well-done mystery adventure. There are hints and clues before the mystery is apparent, such as the reference to Nicolas Flamel on page 77, which much later becomes relevant to the plot.

One of the tests of a good mystery is that, stripped of all peripheral elements (be it the historical aspects in Cadfael books, or the presence of a large dog fond of Scooby-snacks, or the magic of the Discworld series in the detective efforts of Sam Vines), it still works as a mystery. There is a logical, internally-consistent chain of events that leads from start to finish.

That’s the case with this book. You can take away all the magical elements and secret history and similar, replace them with a mundane equivalent, and there is still a perfectly serviceable mystery adventure.

It’s something that a lot of writers (although not the best writers, obviously) forget. If you don’t have a good story as the central element of the book, then it doesn’t matter what chrome you stick on it, the most you can hope for is fleeting genre acceptance. An example of this is the best-forgotten Lord D’Arcy series by Randall Garrett, which purports to be a detective mystery series in a world where magic works, aping the Sherlock Holmes format. The characters rarely achieve two-dimensional status, the attention is always firmly on the nobility (Holmes often involved middle-class and working class elements, even full cases from time to time; crucially, Holmes is not part of the nobility; Lord D’Arcy is, and is written by an American author who clearly has based his historical research on sanitised costume dramas of the period). The plots are turgid (what Doyle would have covered in a short story, Garrett spends an interminable book describing). Surprise, surprise, the Lord D’Arcy series have been long-since (and thankfully) forgotten.

I digress.

The point is that Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone works as a mystery adventure, and the magical trappings of the tale add to the plot, rather than trying to be the plot. It is well-paced, moving along briskly and not getting bogged down in too many explanations (except for the explanation of the rules of Quidditch; self-evidently Rowling didn’t understand how sports actually work).

The characters are largely clichés, but then clichés exist for a reason, and it enables the reader to get a clear idea of the character with a minimum of exposition. It matters more in a longer series, when the reader can reasonably expect to see characters developing as a result of events in the story.

We can also expect the worldbuilding in a longer series to hold together, rather than looking like a load of spaghetti thrown against the wall to see what sticks.

However, analyzing how the series developed is beyond the remit of this review. As a standalone children’s book, and ignoring what the rest of the series became and what rabbit holes Rowling later went down, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone does an awful lot right.

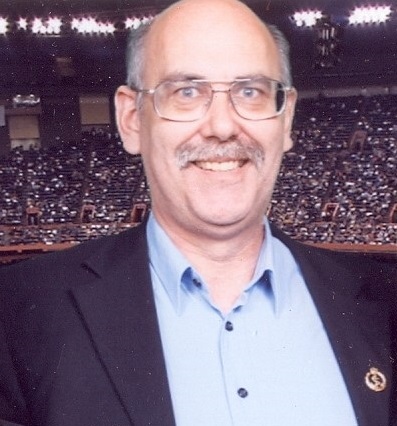

The Snow Marine Speaks – David Flin

I’m David Flin, and I have been for most of my life. I’ve read that with great age comes great wisdom. Well, I’ve achieved the great age (71, and I’ve sidestepped three certain death situations). Wisdom, not so much.

I’ve been a writer for nigh on thirty years now, and in 2020, I concentrated on writing for children and young adults. I also started Sergeant Frosty Publications which publishes books for children and young adults.